|

Still, there are races

to be had, and at 7 p.m. July31 the speedway begins a low

guttural roar that will continue well into the night. First

obstacle for the super-late models is qualifying, then the

Trophy Dash, a race for the six fastest cars that night. Then

there are the heats, then the feature race, a 30-lap

free-for-all with the fastest drivers starting in the back and

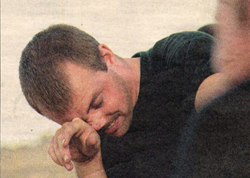

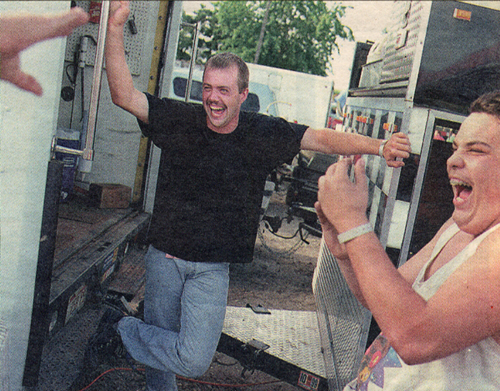

working their way through the pack - that is, if everything goes

as it’s supposed to. Things are not going the way they’re supposed to for Nelms and his crew of Joe Dynek, David Lambe, Allen White and Eddie Wolf. While the other super-late cars roll onto the track, sprint a few laps and fall in line for qualifying, Josh’s car has lost all semblance of a pulse. Nothing’s turning over, and the crew is perched along various sections of the car like in an ER staff slicing into a heart attack victim. All Josh can do is sit, helmet and sunglasses on, inside the car and hope they figure out the problem. While the first cars drive their initial qualifying laps, the No.99 car lies lifeless in the pits. At last, the engine kicks once, then jumps to life. A super-late-model car does not sound like the smooth, steady purr of a sports car, but more irregular, staccato, like a nervous twitch. It’s the primary reason most of the drivers are, or at least claim to be, deaf. To the Nelms racing it is a golden sound. Josh throws mud out from behind the car as he races to the track entrance. The rope is lowered, and he takes his first couple of passes. His second qualifier will place him in the top four. There is no rest for the wicked or for a pit crew, which readies No. 99 for the Trophy Dash, “The Six Fastest Cars for the Six Fastest Laps.” Within 30 minutes, the car is back out on the track again as the clay continues to dry and harden in the wind and sun. Josh sits right in the middle of those six as they all swerve off the corner and bear down for the start of the race. Ten seconds later, less than a lap in, Big Bird has taken flight. He and No. 24 car collide nose to nose, and Josh’s No. 99 car sticks its snout in the air, pulling the rest of the car skyward with it. The race is stymied. |

Josh rights the car,

and the pace pick up again - but only long enough for another

collision between the same two cars. This time, Josh’s is off

the track for good, but he isn’t; he marches down the middle of

the home stretch, fiery, the glare of his eyes visible from the

opposite side of the oval. Helmet in hand, he is pointing,

screaming, at the No. 24 car as it in turn, screams down upon

him.

|